Marcus Rainsford, or The Black Empire of a "Sh*thole"

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

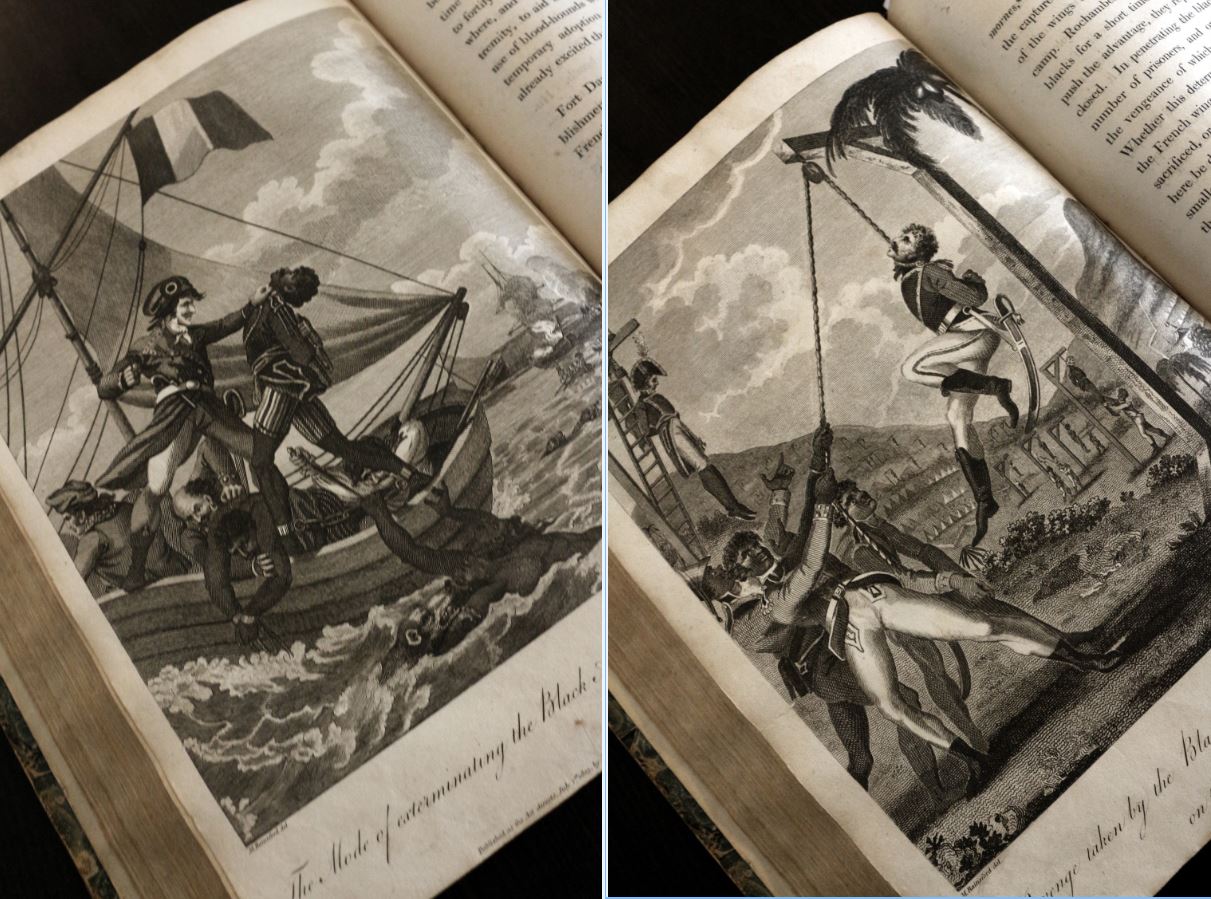

There was little mercy on either side during this brutal war.

Going through a pile of books the other day, I was suddenly attracted to a smelly one. I reluctantly picked it up, considering its yet gorgeous binding. Then, I opened it up, and was instantly overwhelmed by an unexpected smell of... shit! Notwithstanding, I boldly read the title, and all became crystal clear: I had just stepped into a “shithole”. An 1805 book about Haiti? Oh my God!

To be honest, after reading so many history books, I’ve come to the “Trumpish” conclusion that “people have been through shit.” And they’ve had their fair share in the “smelly” island of Haiti, West Indies, indeed. Once a terrestrial paradise—or so we love to figure it out—, it was totally sacked by the first European colonists, who exterminated the Natives before importing hundreds of thousands of African slaves to exploit sugar cane—and that was just a start. During the French Révolution of 1789, the once richest colony of the French empire was hurled into chaos. That’s when the “shit” hit the fan!

Dreadful stories are told about this dark period; from France, signals of blood were sent daily, and many perished in Saint-Domingue—the former name of Haiti—in the most horrid ways. As a matter of fact, that’s the period my “smelly” book focuses on. It yet bears a magnificent title: An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti. It was written by an Englishman, Marcus Rainsford, and printed in England in 1805—it is the first full eyewitness account in English of the Haitian Revolution. And boy, what a gorgeous piece of shit! This in-4° volume is printed on thick quality paper, and richly illustrated. Furthermore, the author had an interesting story to tell since he was sent to Haiti as a recruiter of black troops for the Third West India Regiment—at the time, England tried to take advantage of the disastrous situation of the French colonists. Rainsford actually met with the black hero Toussaint Louverture, responsible for establishing a “black empire” in Haiti. In fact, made Capitaine-Général of the island by Napoléon during the first part of the conflict, he turned renegade before being defeated by the French expedition of 1802. He was eventually sent to France, where he died in exile. This travel was obviously a life-changing experience for Rainsford; and his book is one of a kind, but not necessarily for its wordy contents.

An Egalitarian Black Society

Though quite prized, and hardly ever met in a contemporary binding, this book is disappointing to a certain extent. First, the “historical account” of the island happens to be quite superficial. Second, it suffers from a poor literary style. As a matter of fact, though translated into Dutch and German at the time, it was not reprinted in English until 2013—and although dealing with Haiti, has never been translated into French. One of the publishers responsible for this recent reprint, Paul Youngquist, explains: “Rainsford's history was widely read and well-received on the continent. It's been suggested that, along with contemporary accounts of the Haitian Revolution published in a journal called Minerva, it influenced Hegel's formulation of the master/slave dialectic. The book's characteristic British bias against the French probably explains the absence of his history's influence in France. It's very much a British history of a French defeat at the hands of formerly enslaved Africans..”

There’s something particularly striking about this account. “Rainsford gave an unusually positive evaluation of the new egalitarian society Toussaint L'ouverture labored to create, especially in Cap Français," Paul Youngquist adds. Although not an abolitionist, Rainsford indeed expresses open admiration for black people, which was quite uncommon at the time. About Louverture, whom he personally met, he writes: “His principles, when becoming an actor in the revolution of his country, were as pure and legitimate, as those which actuated the great founders of liberty in any former age or clime.” Black lives mattered in 1805, in a sugar colony? Of course, Rainsford’s partiality towards the French is to be taken into consideration in his praise of Louverture’s “black warriors”. Nevertheless, “he worked closely with black Haitian soldiers,” Paul Youngquist confesses, “and came to respect their intelligence and abilities.”

Shitty dogs

The French Révolution and the abrupt abolition of slavery initiated several years of a dirty, “shitty” war, opposing numerous factions across the island. The French troops even used “hound-dogs”, as Rainsford calls them, against their enemies. Rainsford gives details (unfortunately not as much as wished) about the way they were bred and trained—on black dummies! One engraving in particular, focuses on a creepy training session. Actually, this is where the value of this book truly lies, in its breathe-taking plates. It comes with 2 maps, 1 facsimile and 9 full-page plates. The latter, engraved from Rainsford’s own drawings, are unique. The frontispiece, showing the author standing beside a “private soldier of the Black army”, features some tropical plants in the background. They are full of thick sap, swollen with the eternal principle of life that reigns under the tropics; a sticky heat is rising from the plate, alongside a smell not of shit but of a mixture of intermingled decay and green rebirth. Besides, the characters drawn by Rainsford are of rare physical intensity, and their attitudes quite dramatic.

Some plates strike you like a Tyson’s hook—irrevocably. Such is “Revenge Taken by the Black Army for the Cruelties practised on them by the French.” In the middle of a tropical setting, black soldiers are lynching French ones. The striking attitude of the dying man in the foreground first attracts all our attention, until we slowly realize that there are dozens of “loaded” gibbets spreading away in the background—the engraving is so powerful, you’d swear you actually saw the hanged men’s legs shaking for a second! A vision of horror in a paradisiac setting.

There is another plate entitled “The Mode of exterminating the Black Army as practised by the French”. The scene takes place on a small boat, where a French officer is about to throw a tied Black officer into the sea. The victim is resisting in a very dramatic attitude while bloodhounds swim and chew all around the embarkation! “Such slaughters daily took place in the vicinity of Cape François,” Rainsford writes,“(and) the air became tainted by the putrefaction of the bodies.” In the corner, a French soldier is stabbing a half-drowned and half-devoured dying black man, desperately trying to grab the boat. Last but not least is the plate representing Toussaint Louverture himself. This is a full-length portrait in a truly heroic style—holding his huge sword in his right hand, the Black General wears a “haut-de-forme” hat, and his two thick legs seem to be rooted in the soil of Haiti. We can feel the power emanating from him.

Interestingly, the 2013 reprint boasts of the addition of an original miniature portrait of Louverture by Rainsford—absent from the 1805 edition (see link below). “It was long believed to have been drawn by a French hand,” Paul Youngquist explains. “While researching the edition of Rainsford's history, I stumbled upon it in an exhibition at a museum in South Carolina. Rainsford was enough of an artist to make that possibility plausible, and close expert analysis of the painting style, paper, frame, etc. suggests that it was likely painted by a British miniaturist. While its provenance remains circumstantial, the possibility that Rainsford painted it changes its value.”

Conclusion

People in Haiti “have been through shit”, indeed—and unfortunately they are not through it yet. Was it the price to pay to become the first black Republic ever? Probably. Great historical changes can hardly be but painful—is the American war of independence an exception to this rule? But the Haitians’ humiliated enemies couldn’t afford to step down just like that. It took France 20 years to officially admit their loss, but only after Haiti agreed to pay 150 million gold francs—a fortune. “The economy of the island,” reads an article in the French newspaper Libération (March 2010), “which bled itself dry 125 years long to honour this debt, never recovered from it.” People hardly rejoice when you try to crawl out of your “shithole”; woe to the weak, that’s how men live with men—like wolves, by nature. But only the meanest among us turn bloodhounds. “To call Haiti a shit hole is to degrade not only Haitians,” says Paul Youngquist, “but the ideals of freedom and liberty so many fought, died, and now live for. The remark reveals a monstrous cultural insensitivity equalled only by historical ignorance. The shit Mr. Trump attributes to Haiti and other former colonies was dumped there by the US and its European colonial counterparts in retribution for the audacity of enslaved Africans rebelling against their subjection to create an independent black nation.” In France, we have a saying: “Que les morveux se mouchent.” Guess we could translate it as: “If you smell shit, just wipe your ass.”

Thibault Ehrengardt

Link to the text and plates: archive.org/details/historicalaccoun00rain

Link to the miniature portrait: behindthescenes.nyhistory.org/who-was-toussaint-louverture/