Cartouche 1799, The Journal of a Serial Lover

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

Portrait of a misdated political book that portrays a fake and bigger than life bandit!

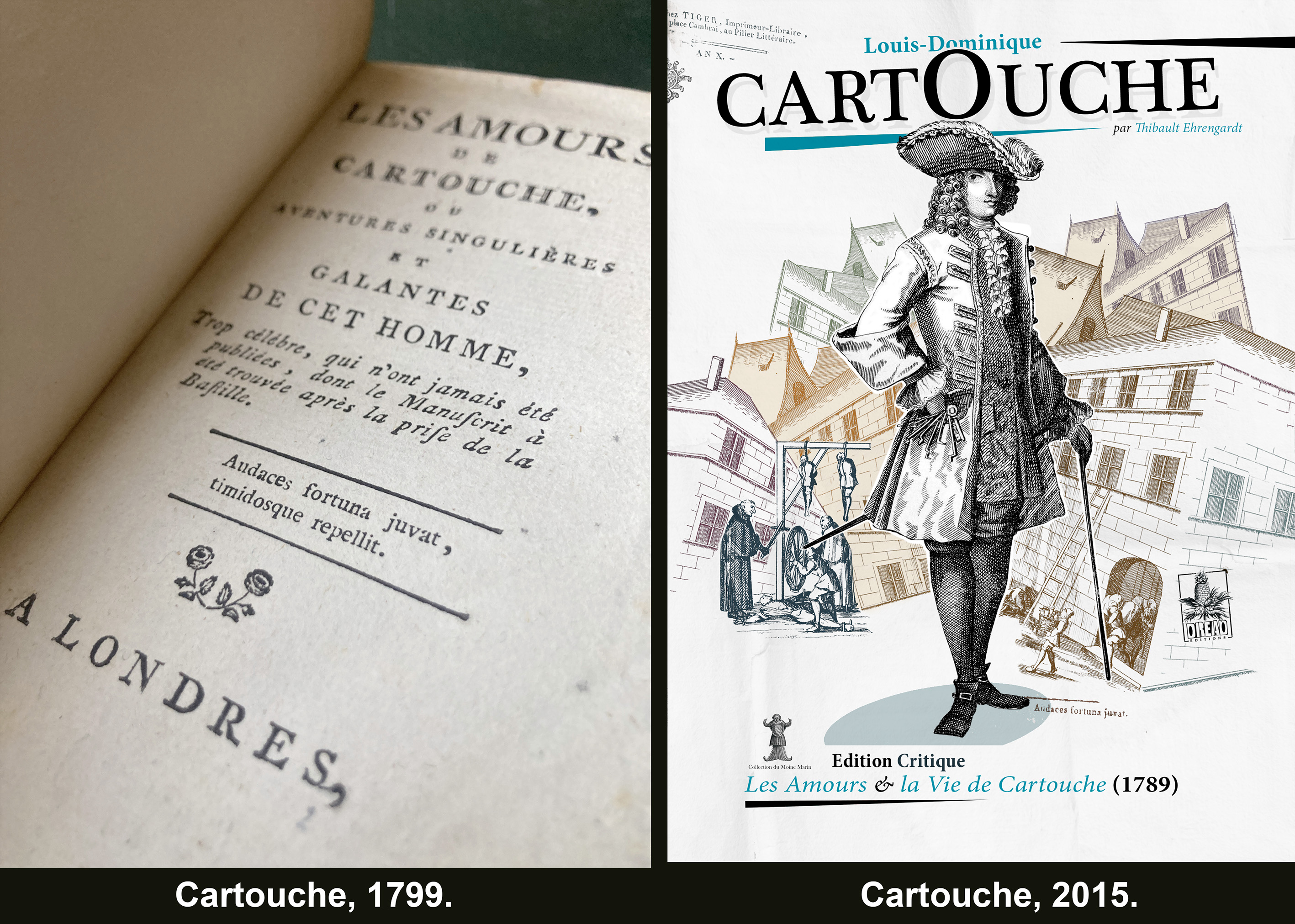

Les Amours de Cartouche...

Louis-Dominique Cartouche was the 1st French public enemy. The rich feared him, but the others liked him because he gave them the opportunity to laugh at an incompetent and corrupted regime. Cartouche was broken alive on the wheel in 1721, as the scapegoat of a deteriorating society, and hundreds of his alleged accomplices were executed in his wake. His “official” biography, La Vie et le procès de Cartouche...* (Paris, 1721) depicts him as a villain—but things changed with the Révolution (1789). That’s when a discreet and somehow forgotten little book was anonymously published in London—more likely Paris. This revised history turned Cartouche into the romantic figure that he still is in the French popular culture.

Post Révolution Book

Les Amours de Cartouche... (Londres, no date) is Cartouche’s fake and posthumous autobiography. Probably because of the lewd passages, most historians have overlooked its importance, but when I realized it had shaped the myth as we celebrate it today, I did my best to rehabilitate it—I reprinted it in 2014. A modest effort, I must say—but it was a start. The first edition of Les Amours de Cartouche... is very rare. It was, the title page reads, printed in London—a forgery, worthy of Cartouche. And it came without a date. At one point, someone decreed that it was published in 1760. Might be Sotheby’s that sold one of the only two copies that went for auction over the last 30 years (source: the Rare Book Transaction History)—sold for £230 in 1995. I guess most auction houses have reproduced Sotheby’s’ description, and J. Rustin, in his scholarly article L’Histoire véritable dans la littérature romanesque du XVIIIe siècle français (Persée, 1966) did no better. It shows that he never actually read it, or held a copy in his hands, as the full title says it all:

Cartouche’s Love Affairs, or the Singular and Gallant Adventures of this too famous a man, that have never been published, the manuscript of which was found in La Bastille after it was taken.

La Bastille was the royal prison located in Paris. It was taken in 1789, as the birth act of the Révolution. Although the later editions, including Tiger’s, mention that the said manuscript was actually retrieved from a “shed in Bicêtre (a prison) following the death of Duchatelêt, Cartouche’s former accomplice who gave him away,” the first edition remains sovereign. But it came without a date, so maybe there is an edition from 1760? This is clearly not the case, as Sotheby’s copy is easily identified—it once belonged to Archibald P. Primrose (1847-1929), a former British Prime Minister and a noted bibliophile. He even wrote, on the last page: “August 1905. Amusing but of course spurious.” And it is the copy I’m holding in my hand while writing this article—so, no doubt, it was published after 1789. The earliest Tiger’s edition I could find is from Year X—1802. The first edition uses the “f” symbols to reproduce the “s” sound that was abandoned around the year 1800, so 1799 is a reasonable guess. As a matter of fact, this little book has a post-1789 tone. We don’t know who wrote it, but the “esprit”, the style or the use of semicolons, are the works of a talented writer. Doing justice to the epic adventures of Cartouche, our author turns him into a gallant French Robin Hood, who stands against the evil “ancien régime”. He was none of that, of course—but fiction is sometimes stranger than truth.

Cartouche’s story was linked to fiction from the start—the playwright Legrand went to visit him in prison to write Cartouche, ou les Voleurs (Paris, 1721)**, and gave the first representation in Paris while the robber was in jail, waiting to be executed! At the time, fiction came as a way to somehow go round censorship—in 1799, the royal censors were no more, and books sprung from every street corner, as the number of booksellers doubled between 1780 and 1800. At last, Cartouche could express himself, or be expressed, in full swing! That’s what this incredible little book is all about. Forget about the made-up parts—there are as many as in the “official” biography—, read between the lines and you’ll find; if not the “real” Cartouche, at least the true myth.