Old time people used to say, sweet nanny goat have a running belly! This Jamaican saying that Bob Marley used for his first hit song (Simmer Down, 1963) means: the grass is always greener on the other side—but it will give the greedy goat a running belly, or diarrhoea. Once despised, Jamaican patois and Anancy stories are crucial parts of the island culture—as a little book from 1873 shows, they’ve always been.

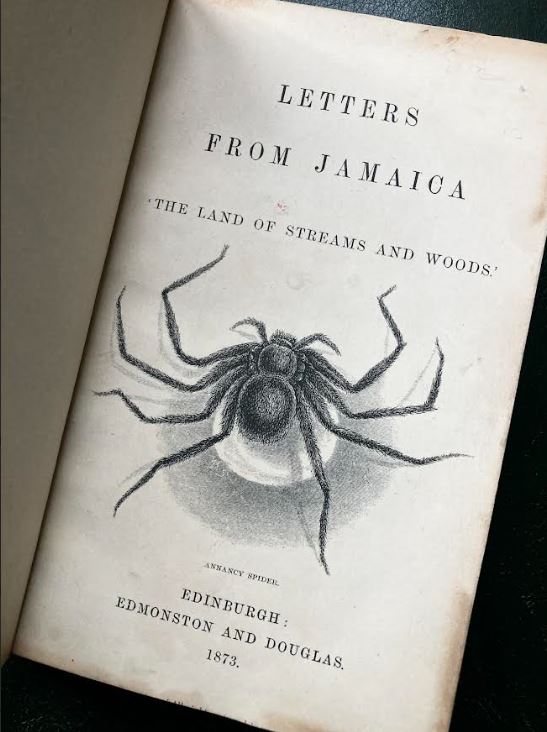

Letters From Jamaica (Edinburgh, 1873) is a small book that “pretend(s) to being nothing more but a truthful record of a traveller’s impression of Jamaica and its people”, its author writes. It consists in a series of short picturesque articles, written by Charles Joseph Galliari Rampini (1840-1907), a Scottish lawyer who knew Jamaica well. His obituary (findagrave.com) states: “A year later (1866), he was appointed a Stipendiary Magistrate Jamaica; in 1867 became District Court Judge at Port Antonio; in 1868 at Maudville(sic), and in 1876 at, Kingston.” Beyond the contempt that is to expected from such a traveller, Rampini was clearly interested in many aspects of the Negro culture—including obeah (or voodoo, “far from uninteresting subject,” he says), and what we now call “patois”. This language is a sort of “broken English” invented by the slaves. The Jamaican intellectuals love to emphasize its African heritage, but “patois” is mostly based on phonetic distortions, grammatical simplifications and lyrical emphasis. Let’s remember that it was a survival tool. Its creativity has always fascinated the outsiders such as Matthew “The Monk” Lewis, who went twice to Jamaica in the early 19th century, or such as our friend Rampini. Both were particularly interested in an old spider that goes by the name of Anancy.

Anancy and the Bakras

Once the scorned mark of the lower social class, “patois” has now become a source of pride. It’s partly due to the iconic work of Louise Bennett (1919-2006), better known as Miss Lou. She compiled many traditional stories and recited them in “patois”. “The principal hero of this autochthonic literature,” Rampini writes, “is the large black Annancy(sic) spider. He is the personification of cunning and success.” On the website of the Harris County Public Library, Crystal Mosley adds in 2023: Anancy “derived from traditional Akan culture. He is usually the depiction of the consequences of your bad actions even though his stories are most based around humor. He was believed to have been born through Ashanti legend in Ghana.” Rampini wasn’t the first one to mention “Anancy stories”, as the brilliant Matthew G. Lewis mentions (and reproduces) some of them in his must-read Journal of A West-India Proprietor (London, 1884). He notes that “it seems an indispensable requisite for a Nancy-story, that it should contain a witch, or a duppy, or, in short, some marvellous personage or other.” As the author of The Monk, he probably understood that. To make it short, Anancy stories are fairy tales—but they come from the African tradition. “It is essentially the literature of a race, not of a nation,” Rampini says. No matter what happens to Anancy, it happens to him in patois—an essential point, as they come from an oral tradition. Both authors noted down a few Anancy stories, including Anancy and the Tiger, etc. They’re pleasing but sound a bit flat without the tone and the Jamaican accent.

Patois and proverbs

Rampini’s observations are pleasing, rarely original—he came to Jamaica a few years only after the crucial events known as the Morant Bay rebellion. The freed black people rebelled against the colonial power, and two leaders were hanged, who have since become National heroes. Rampini sweeps the events from the back of his hand with contempt. But I guess he was trying to sound as witty as Lewis, whom he had clearly read, only succeeding in being sarcastic and despiteful. At the end of the day, the Negro culture is what fascinated him the most in Jamaica, especially the language. He even lists some patois expressions that reminded me of my old vinyl records!

On the left some expressions listed by Rampini, and on the right, the reggae songs using them one century later.

-

Cock mouth kill cock: Justin Hinds, Cock Mouth Kill Cock (1975).

-

Cuss-cuss (calling names) no bore hole in my skin: not exactly the same but Cuss Cuss is a classic song by Lloyd Robinson (1969).

-

Duppy (ghost) know who fe frighten: Demarco, Duppy Know Who Fe frighten (2014).

-

Greedy (greed) choke puppy: The Wailers, Craven Choke Puppy (1972).

-

Play wi’ puppy, puppy lick you face: The Gladiators, Rich Man Poor Man (1976).

-

Water more than flour: Johnny Osbourne, Water More Than Flour (1979). It means that times are hard and that the soup is made more of water than flour.

-

When pigeon merry, hawk deh near: The Wailers, Simmer Down (1963). Used as “chicken merry, hawk deh near” to mean that while you’re enjoying life, danger is never far.

-

You shake man hand, you no shake his heart: Horace Andy, See A Man’s Face (1972). Not exactly the same, as Andy sings: you see a man’s face, but you don’t see his heart...

So those patois expressions were still used in Jamaica a century after Rampini’s passage, and were even used in popular songs. As they say in Jamaica, ole time something come back again...

Thibault Ehrengardt

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0372eeb9-97e1-47b2-baca-b3287d4704ee.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8f9ce440-b420-4407-8293-eb8e1b38ca19.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/71bb9667-5d66-4aa8-96a2-9880c74a7a26.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 57<br>[Album and Treatise on Hinduism], manuscript treatise on Hinduism in French, 31 watercolours of Hindu deities, Pondicherry, 1865. £3,000-4,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 57<br>[Album and Treatise on Hinduism], manuscript treatise on Hinduism in French, 31 watercolours of Hindu deities, Pondicherry, 1865. £3,000-4,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/f70b3790-9b4a-4990-b402-f0322021c0de.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 62 Allan (Capt. Alexander). <i>Views in the Mysore Country,</i>

[1794]. £2,000-3,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 62 Allan (Capt. Alexander). <i>Views in the Mysore Country,</i>

[1794]. £2,000-3,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/ad2cf7b4-4d93-4231-a956-b440583b39b3.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 123<br>D'Oyly (Charles). <i>Behar Amateur Lithographic Scrap Book,</i> lithographed throughout with title and 55 plates mounted on 43 paper leaves, [Patna], [1828]. £3,000-5,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 123<br>D'Oyly (Charles). <i>Behar Amateur Lithographic Scrap Book,</i> lithographed throughout with title and 55 plates mounted on 43 paper leaves, [Patna], [1828]. £3,000-5,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/5651043b-3c0d-4e2c-931f-72133bda9b36.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 205<br>Marshall (Sir John) and Alfred Foucher. <i>The Monuments of Sanchi,</i> 3 vol., first edition, 141 plates, most photogravure, [Calcutta], [1940]. £3,000-4,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 205<br>Marshall (Sir John) and Alfred Foucher. <i>The Monuments of Sanchi,</i> 3 vol., first edition, 141 plates, most photogravure, [Calcutta], [1940]. £3,000-4,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8c8244b7-4573-44d3-9c70-e0d3a3ed3cc4.jpg)