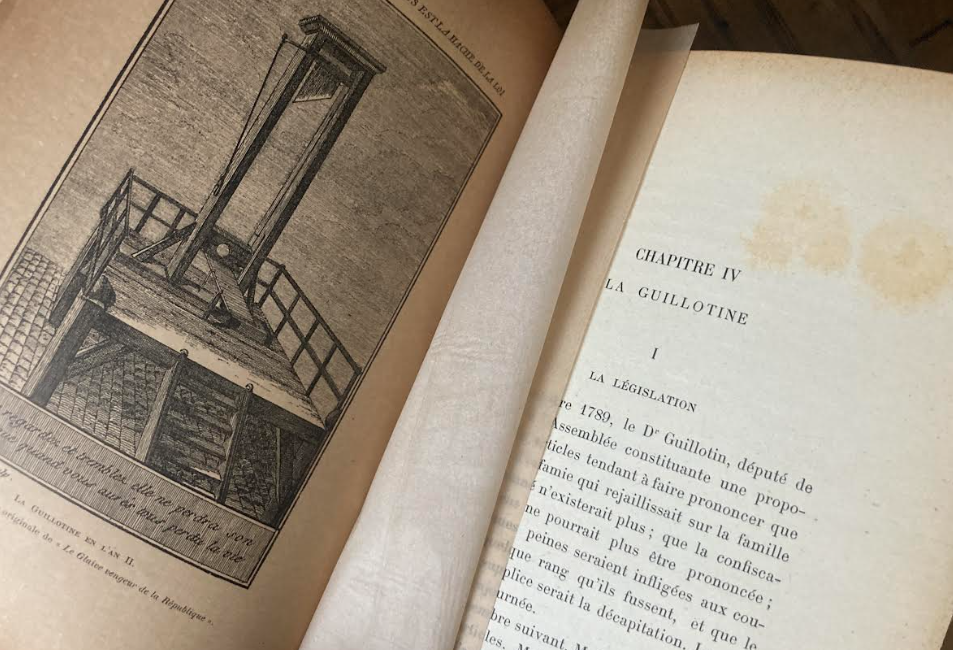

When Robert Badinter (1928-2024) had the death penalty abolished in France in 1981, he didn’t destroy the last guillotine, but stored it instead. He wanted it to be later exhibited in a museum. Later is now, and the “death instrument” has just reappeared at the Muceum, in Marseille. And boy! It looks as dreadful as ever. Meanwhile, Robert Badinter’s just entered the Panthéon (where the great men are laid to rest), so I guess it’s time for us to open La Guillotine, by G. Lenôtre (Paris, 1883).

The Last of the Guillotinés

September 10, 1977. 4:00 AM. Prison Les Baumettes, in Marseille. Hamida Djandoubi drinks his last drink and is tied to the guillotine. Monique Mabelly, a senior magistrate, writes: “I hear a loud noise, I turn around—blood, a lot of blood, real red—the corpse has dropped into the basket. In the twinkle of an eye, a life is cut off. The man who was speaking a minute ago is now but a blue pyjama in a basket.” This was the very last execution that took place in France as the death penalty was abolished a few years later. 1981: Robert Badinter, a lawyer traumatized by one of his clients’ execution in the early part of his career, became Minister of Justice and sent the guillotine to retirement. Lots of people were relieved, who saw the guillotine as a symbol of barbarity. Yet, when the Assembly had decreed, on May 3, 1791 that “those sentenced to death will lose their heads,” it was social progress. As a matter of fact, the next thing the Assembly did at the time was to find the softest way to have a head severed. That’s when the good Dr. Guillotin intervened.

Dr. Guillotin’s Daughter

Dr. Guillotin (1738-1814) is described by G. Lenôtre in La Guillotine, as “a moderate, a philanthropic thinker, and a gentleman.” Unfortunately, he gave his name to one of the deadliest instruments of all times. “It is,” Dr. Bourru said during Guillotin’s funeral oration, “so difficult to work for the good of mankind without suffering some consequences.” But did Guillotin invent the guillotine? Well, its origins are obscure—some say it was used in ancient China, others that Guillotin built it after some Italian engravings from the 16th century. “Dr Louis, perpetual Secretary to the Academy of Surgery,” Lenôtre writes, “clearly established that a likely machine was in use in England during the 18th century.” But the machine that changed the face of French history was designed by Guillotin. The directive of the Assembly was to render the execution “as painless as possible.” Thus, Dr. Guillotin didn’t design a “death instrument”, but one of equality and humanity. Indeed, following the Révolution (1789), all citizens were equal before the law... and before death. Bygone were the days of tyranny when the Nobles were beheaded, while the outcast were hanged or broken alive on the wheel—from now on, all stood equal at the foot of the guillotine. The Assembly also asked the executioner Sanson* for advice. The legend has it that he was thinking about it when his German friend Schmidt (who built the first guillotine) hastily drew a sketch on a piece of paper—thus the guillotine was born. But Lenôtre doesn’t give much credit to this version, directing us to Dr Louis’ report instead, which he addressed to the Assembly in 1791. “Building such a machine will be quite easy,” Dr Louis writes, “and it can’t fail to reach its aim: the beheading shall be immediate, according to the spirit of the new law.” Good.

Terror Instrument

The guillotine’s very first victim was a common criminal named Nicolas-Jacques Pelletier, who was beheaded on April 25, 1791. The event attracted a huge crowd, but the show was disappointing. “The people didn’t see a thing. It went too fast,” the Chronique of Paris reports the next day. Yet, the guillotine soon became the main character in a bloody national tragedy. “We can’t help but wonder what would have happened if it wasn’t for the guillotine,” Lenôtre writes. “Of course, the uprising and the massacres of September 1792 would have taken place all the same; but it’s a sure thing that without the guillotine, the revolutionary court wouldn’t have been as efficient. The people in Paris wouldn’t have witnessed so many executions—Sanson himself declared it impossible to execute so many people the old-fashioned way.” The guillotine rapidly became the creepiest instrument of terror, as it was sent all over France to discipline the enemies of the Republic. The executioners were wanted, had to travel with their own guillotine to answer the pressing requests of local authorities. Lenôtre tells the story of a few psychopaths who were then having the time of their lives. People like Joseph Lebon in Arras, or Javogue in Feurs—the latter would “walk the streets entirely naked to revive, so he said, the ancient Republican simplicity. During public meetings, he preached sharing women, and advocated prostitution of young women, as well as incest. He sent a woman who had refused him her favours to the guillotine. He made her walk half-naked to the scaffold. He stopped her on her way, and told her she looked beautiful.” A “terror instrument” isn’t enough to implement terror; you also need “terrorists”.

Holy Guillotine Kill For Us

“Madness has so much contaminated the minds of the French that the guillotine generated her own admirers and followers,” Lenôtre writes in the chapter The Cult of the Guillotine. One Gateau, an official member of the revolutionary government, mentions the “holy guillotine” in his letters, as the instrument of the “beneficent Terror.” It was included in several official ceremonies, and several songs were written in its honour. Lenôtre reports one of them:

Holy guillotine, protector of the patriots, pray for us,

Holy guillotine, terror of the aristocrats, protect us,

Lovely machine, pity us,

Admirable machine, pity us,

Holy guillotine, deliver us from our enemies.

Lenôtre admits: “my reader (...) must have felt disgust and discomfort at some points”—but it was, he adds, necessary to tell about the dark side of history. It was “with a certain relief” that he wrote “The end” at the bottom of the last page of this book. France, on the contrary, wasn’t done with Dr Guillotin’s savage daughter yet.

Constitutional violence

The advent of the guillotine in 1791 was social progress; so was its retirement in 1981. As Robert Badinter put it in front of the National Assembly: “Thanks to you, the French justice will never kill again.” 35 years later, France celebrates her abolitionist, but in the middle of self-congratulations, and as the legacy of the Lumières fades by the hour, some voices rise to speak not on the behalf of the unfortunate culprits. They remind us that among those saved from the guillotine by Badinter was Patrick Henry—the murderer of a 7-year old boy; or Norbert Garceau—he had strangled to death a 15-year old girl, was convicted a first time, released, and then murdered a young girl. Closer to us, is the heart-breaking case of the 8-year old Maëlys, abducted and murdered by Nordhal Lelandais. Justice didn’t send Lelandais to the guillotine, because we know better—he was sent to prison; there he exercised his rights to change his name (now Périnet), and to correspond with a woman from the outside. The latter came to visit him in prison, had sexual intercourse with him, and is now with his child. Justice, it seems, has higher interests beyond the understanding of the vulgar individuals—or the victims. They are too emotional—just like Monique Mabelly during Djandoubi’s execution, or like Badinter during his client’s? Well, don’t get smart, now. If Lelandais is having sex in prison while Maëlys forever lies in her tiny grave, there’s nothing personal—it’s for the greater good.

Thibault Ehrengardt

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> HAMILTON, Sir William (1730-1803) - Campi Phlegraei. Napoli: [Pietro Fabris], 1776, 1779. € 30.000 - 50.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0372eeb9-97e1-47b2-baca-b3287d4704ee.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> [MORTIER] - BLAEU, Joannes (1596-1673) - Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie. Amsterdam: Pieter Mortier, 1704-1705. € 15.000 - 25.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8f9ce440-b420-4407-8293-eb8e1b38ca19.jpg)

![<b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000 <b>Il Ponte, Feb. 25-26:</b> TULLIO D'ALBISOLA (1899-1971) - Bruno MUNARI (1907-1998) - L'Anguria lirica (lungo poema passionale). Roma e Savona: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, senza data [ma 1933?]. € 20.000 - 30.000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/71bb9667-5d66-4aa8-96a2-9880c74a7a26.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 57<br>[Album and Treatise on Hinduism], manuscript treatise on Hinduism in French, 31 watercolours of Hindu deities, Pondicherry, 1865. £3,000-4,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 57<br>[Album and Treatise on Hinduism], manuscript treatise on Hinduism in French, 31 watercolours of Hindu deities, Pondicherry, 1865. £3,000-4,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/f70b3790-9b4a-4990-b402-f0322021c0de.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 62 Allan (Capt. Alexander). <i>Views in the Mysore Country,</i>

[1794]. £2,000-3,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 62 Allan (Capt. Alexander). <i>Views in the Mysore Country,</i>

[1794]. £2,000-3,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/ad2cf7b4-4d93-4231-a956-b440583b39b3.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 123<br>D'Oyly (Charles). <i>Behar Amateur Lithographic Scrap Book,</i> lithographed throughout with title and 55 plates mounted on 43 paper leaves, [Patna], [1828]. £3,000-5,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 123<br>D'Oyly (Charles). <i>Behar Amateur Lithographic Scrap Book,</i> lithographed throughout with title and 55 plates mounted on 43 paper leaves, [Patna], [1828]. £3,000-5,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/5651043b-3c0d-4e2c-931f-72133bda9b36.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 205<br>Marshall (Sir John) and Alfred Foucher. <i>The Monuments of Sanchi,</i> 3 vol., first edition, 141 plates, most photogravure, [Calcutta], [1940]. £3,000-4,000 <b>Forum, Feb. 19:</b> Lot 205<br>Marshall (Sir John) and Alfred Foucher. <i>The Monuments of Sanchi,</i> 3 vol., first edition, 141 plates, most photogravure, [Calcutta], [1940]. £3,000-4,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8c8244b7-4573-44d3-9c70-e0d3a3ed3cc4.jpg)